Big Brother is watching you: Fascism is born in Italy

In the first half of the 20th century, Europe was one seriously messed up place. It was a time that constituted the last bastion of the old, crumbling Empire building European states. Every tribe on the continent feared and loathed every other tribe. They’d all been fighting each other for pretty much most of the last one and a half thousand years or so – ever since the collapse of the Roman Empire in fact. The only good foreigner was a dead foreigner as far as most Europeans were concerned. Preferably with knitting needles sticking out of his eyeballs. The increasingly unhinged paranoia and encroaching senility of the old European elite led the continent blindly into the First World War – the most destructive war in history up until that time and just about the most pointless, so far as what anybody actually got out of it.

Economic stagnation followed, and then the Great Depression. Europe might as well have been back in the Dark Ages. The stench of revolution was in the air. People were pissed. They were prepared to get behind any ideology that appeared to offer something more glamorous and interesting than what they had at present. Just about anything, in other words. It was like Judaea at the turn of the millenium. People would listen to any deluded nutjob willing to get up on a soapbox in the market square and claim to be the son of God. Turmoil, upheaval and disillusion will do that to a people. That was Italy in the 1920’s. Into that great big desire for any alternative stepped Mussolini and his ideas about fascism – the most oppressive (and the most camp) form of government to come out of the 20th century. Fascism had a bit of everything: dressing up in uniform, wearing medals, putting on silly hats, marching around, saluting the flag and admiring gigantic propaganda posters featuring homoerotic imagery of muscular, Spartan supermen who would be the fascist worshipping utopians of the future. The people found it all very exciting. This is the story of how Mussolini pranced into power and captured the peoples’ imagination, only to be savagely hacked to pieces for his comic level of incompetence during World War II.

BENITO MUSSOLINI

Country of Rule: Italy

From: 31 October 1922 – 25 July 1943 and 26 September 1943 – 26 April 1945

Official Title: His Excellency Benito Mussolini, Head of Government, Duce of Fascism, and Founder of the Empire.

Demise:Just two days after deserting his post as Duce of the Italian Social Republic – a Nazi puppet regime in the North of Italy established after Italy’s official surrender to the Allied Powers – Mussolini was executed by Walter Audisio of the National Liberation Committee. Mussolini was shot twice in the chest at close range. His body was then dumped in Milan’s Piazza Loreto, where it was shot at, kicked and spat on by members of the public. The body was then hung on a meat hook from a gas station roof, where the public continued to throw stones at it while screaming abuse. Mussolini was 61 years of age.

Death Toll: Political executions in Italy under Mussolini were surprisingly infrequent for a Despotic state. It’s estimated that approximately 400 political prisoners were put to death.

If we include war casualties, however, it tells a rather different story. Perhaps as many as 400,000 people were killed during Mussolini’s occupation of Ethiopia, depending on which sources your read. And Mussolini’s rather futile entry into World War II resulted in the deaths of some 450,000 Italians (including about 145,000 civilians) along with an unspecified number of casualties inflicted on the Allied Powers by Italian forces.

Towards the end of the war, Italy began collaborating in the Nazi extermination program, turning over some 8,000 Italian Jews to German authorities for execution in death camps.

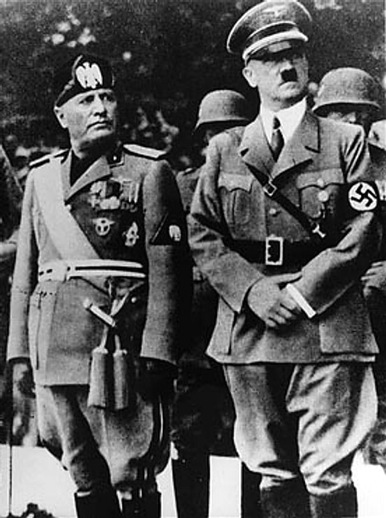

Physical Defects: Not much beyond the most typical Despotic curse – Mussolini was a short-arse. His 5’6″ was considered fairly diminutive even by the standards of the day. Hitler – not exactly an athletic he-man himself at a very pudgy 5’9″ – looked like a basketball player standing next to Mussolini. Beyond that there was always something vaguely camp about Mussolini. As is very much the case with so many Despots – particularly in the 20th century – Mussolini’s regime appeared to be as much about getting dressed up in uniforms, medals and flamboyant hats to march around in as much as anything.

Mussolini: Hitler's junior partner in more ways than one

Bio: Born the son of a revolutionary blacksmith and named after a Mexican reformist President, Mussolini was always likely to become involved in political activism – albeit in a fashion surely never envisaged by his pro-anarchist father. He was raised as a confirmed socialist and worked as a political journalist in his younger days, for publications with names like “The Future of the Worker” and “Class Struggle”. When just 18 years old, Mussolini participated in a socialist riot in protest over Italy’s expansionist war in Libya, earning himself a five month stint in prison. It was an incident in marked contrast to Mussolini’s future stance as a military expansionist and Italian nationalist.

When The Great War broke out in 1914, Mussolini was initially opposed to Italy’s involvement. However, he came to view the war as an opportunity for social renewal, involving the overthrow of capitalist government. He become a staunch war advocate, quite in opposition to his socialist peers. Mussolini was eventually conscripted into the Italian army, but only saw about nine months worth of action. He contracted paratyphoid fever and was seriously wounded when a mortar shell accidentally exploded in his trench, earning him a discharge from active service.

Mussolini returned from the war with his political outlook radically altered. He became disillusioned with socialism, considering it increasingly irrelevant and impractical as a force for political change. What was needed was greater autocracy, a man “ruthless and energetic enough to make a clean sweep” of Italy’s stagnant, crumbling economic and social landscape. At some point, Mussolini began to see himself as precisely that kind of man.

By 1919, Mussolini had gathered around himself a number of supporters, drawn from the ranks of war veterans, ex socialist revolutionaries and various future theorists. It was a time of immense social upheaval in Europe, when any number of outlandish political and utopian theories were suddenly taken very seriously. Mussolini’s group became known as the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Combat Veteran’s League) from which an emerging ideology, “fascism” was drawn. The term was meant to have connotations with the Roman fasces – a standard used as a symbol of officialdom in the Roman Republic. It represented authority, discipline and unity. More chimerical and obtuse than the comparatively well developed socialist theories of Karl Marx, with its fetishisation of emblems, “visions” and self glorification, Italian fascism became one of the most influential political movements of the 20th century. Its iconography and resort to the manipulation of imagery and public perception over concrete policy has become endemic to the modern age, among otherwise widely divergent political systems.

Like most political terminology in current usage, however, the word “fascism” has so become so frequently misapplied as to no longer convey anything but the most debased meaning. It’s now shorthand for any state activity that could be construed as authoritarian. Or even any activity that is merely disagreeable. As George Orwell recognised as early as 1944:

“…the word ‘Fascism’ is almost entirely meaningless. In conversation, of course, it is used even more wildly than in print. I have heard it applied to farmers, shopkeepers, Social Credit, corporal punishment, fox-hunting, bull-fighting, the 1922 Committee, the 1941 Committee, Kipling, Gandhi, Chiang Kai-Shek, homosexuality, Priestley’s broadcasts, Youth Hostels, astrology, women, dogs and I do not know what else … Except for the relatively small number of Fascist sympathisers, almost any English person would accept ‘bully’ as a synonym for ‘Fascist’. That is about as near to a definition as this much-abused word has come.”

In actual fact, most of the things branded as “fascist” these days would not be recognised as such by Mussolini, the movement’s founding father. As originally conceived, fascism is perhaps more closely related to the kind of ideas expressed in Plato’s The Republic than it is to any modern conception of the word. It’s an ideology in which the aspirations of the individual are entirely subsumed by the aspirations of the state. Personal wellbeing is only considered relative to the wellbeing of the social structure. Individual freedom is rejected as ultimately harmful, with life conceived as unceasing duty and sacrifice to the good of the state. In Plato’s idealised conception, such a society would be dedicated to the pursuit of justice and morality. The fascists were more cynical. The state would be mobilised and united for the pursuit of practical political goals. Lasting peace was seen as unrealistic and counter-productive, with the natural world order being one of perpetual struggle and competition between various nation states. The strength of the state was to be maintained by a unity of purpose: everybody moving towards a single goal based around faith in the natural superiority of their nationality, and in the cult of personality invested in a charismatic, all powerful father figure as the leader and guiding force. It’s easy to spot the kind of influence such ideas had on men like Hitler.

Yet it’s still possible to detect the influence of socialism in early fascist thought, particularly with regard to economic policy. Communism was generally rejected (and even demonised) by the official ideology, but fascism advocated strong state intervention in economic affairs, including the implementation of livable minimum wages, shorter working days and worker representation in the affairs of industry. In this sense, although the early fascists were advocates of authoritarian government with limited personal freedom, they were much further to the left than the modern free market democratic systems of today, at least so far as economic policy was concerned. Under a fascist regime, a man might be expected to sacrifice his personal liberty in the interest of maintaining strict social order, but he was unlikely to go without a job. That’s not an unimportant consideration in the dissolution, despair and economic stagnation of post World War I Europe.

Amid the grim state of malaise afflicting Italy at the time, Mussolini’s declarations of authoritative and decisive rule mixed with practical and populist concerns proved to be a potent combination. He was a charismatic public figure and skilled orator, allowing him to rapidly mobilise strong public support. Along with the popular following went the muscle. The Fascists formulated gangs of disaffected young men into a paramilitary organisation: the MVSN – “The National Security Volunteer Militia” or “Blackshirts” – as they were more commonly known. Nominally, the Blackshirts were supposed to restore order to Italian streets. In practise, they became a tool of intimidation, using violence to stamp out rival political movements.

Ostensibly, Italy was still ruled by a monarchy under King Victor Emmanuel III, although in practise a democratic parliamentary government, headed by Prime Minister Luigi Facta, was responsible for the day-to-day affairs of state. At this point, however, both the Monarchy and the Parliament were weak and demoralised. Fearing the revolutionary potential in any conflict, they gave Mussolini’s “Blackshirts” a free hand to act as and when they wanted. By 1921, the Fascists had effective control over much of rural Italy. The Fasci Italiani di Combattimento evolved into a formal political party – The National Fascist Party – and Mussolini was elected into the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of Italian Parliament).

In 1922, a Confederation of socialists and labour union activists called for a general strike, as a last ditch protest against the growing influence of the Fascists. It couldn’t have been a more stark illustration of Italy’s political divide, its ineffectual government, and eventual fate. Mussolini openly challenged the Italian government to do something about the situation, which sat back and refused to become involved as the Fascists sent in some 40,000 Blackshirts and other assorted supporters to smash up the strikes. Mussolini then demanded that the government be “given to us, or we will seize it by marching on Rome.” With the Fascist militia rapidly approaching, King Victor Emmanuel III caved in, severing all ties with Prime Minister Luigi Facta and personally inviting Mussolini to Rome to head the formation of a new government. Officially, the King was still recognised as the head of state, but in actual practise he was totally marginalised as Mussolini immediately began implementing his envisaged Fascist regime.

In the early years, Mussolini intended to retain at least the facade of democracy. Elections were held in 1924, with Mussolini winning a 64% majority in what was largely perceived to be a wholesale fraud. Prominent socialist politician, Giacomo Matteotti, became the most vocal critic of the sham election, as well as the principles of fascism in general. On 10 June, a group of fascist supporters attempted to kidnap Matteotti. In the ensuing struggle, he was brutally stabbed to death with a carpenter’s file. The level of Mussolini’s involvement in the murder is very much a matter of debate. In any event, the incident sparked an early crisis of leadership, as there was immediate protest among the opposition members of Parliament. However, the opposition couldn’t muster any cohesive, sustained resistance, and Mussolini was urged on by his own MSVN leaders to seize the opportunity to stamp them out. Blackshirt units were sent out to beat up opposing Parliament members and break up any printing press distributing critical material. The resistance was swept away with surprising ease, and overall control ceded to Mussolini with a minimum of fuss. At a minimal display of force, the opposition lined up subserviently behind Mussolini. Any pretence at democracy was done away with in a swift stroke.

Over the next few years, Mussolini consolidated his total control of the government by banning all opposition parties and effectively stripping the Parliament of any constitutional powers. Again, all this was accomplished with an almost uncanny lack of resistance. The country had been thoroughly cowed by years of apathetic stagnation and effectively handed over the reins of power upon demand. The public was placated by a few populist gestures such as the implementation of a minimum wage.

The bulk of Mussolini’s efforts were bent on creating a cult of personality surrounding himself. The Fascists became the nascent masters of 20th century political propaganda, the lessons of which have since been absorbed throughout the world, in every form of government. Mussolini was portrayed as a heroic superman, a can do Mr. Fixit who never slept, never made the wrong decision and was capable of solving any problem with simple and practical application. Fascism was portrayed as the government of the future, supplanting socialism, democracy and any previous form of government. It would create a future super state of glorious, utopian dimensions. Italy would recall the glory days of the Roman Empire and once again become the vanguard of the world. In actual practise, however, fascism was less than coherent as a practical political system. It was a catch-all contradictory ideology, rejecting communism and capitalism but drawing from elements of both of them, along with another half dozen, half conceived theories.

In effect, Italian fascism boiled down to an oppressive police state. Far from being the lean, all-purpose, energetic system of rapid accomplishment it was made out to be, fascism became bogged down in a monstrous bureaucracy, with endemic corruption and the attendant inefficiency. The media was tightly monitored and controlled. Mussolini personally appointed sympathetic newspaper editors. He instituted the OVRA – Organisation for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism – a secret police force. Some 5,000 OVRA agents were in operation, constantly surveilling the population for indications of dissidence. An estimated 4,000 people were arrested and imprisoned or deported for political reasons under Mussolini’s regime. In actual practise, however, there was little serious, organised resistance against the fascist government. This perhaps explains why there were so few political executions in Italy under Mussolini in comparison to other Despotic states. They did take place, but there were none of the mass purges that became commonplace throughout the rest of the 20th century. It was an oppressive regime and far from benign, but not especially murderous towards its own population.

In actual fact, Mussolini was a popular figure with the Italian public for much of his regime. Although his economic programs were often clumsy and inefficient, they did at least get people back in employment, bringing a measure of stability back to Italian society that had been all too lacking in the preceding decades. And while the Great Depression was biting deep throughout much of the world, Italy was beginning to get back on its feet. International support for Mussolini was generally approving, bordering on the rapturous in some quarters. British and American politicians queued up to lionise Mussolini for helping to prevent the spread of communism in Europe. “The wops are unwopping themselves” – crowed Fortune magazine in 1934. It’s sobering to consider that our supposedly enlightened Western democratic states were at one point largely celebratory of the rise of fascism, at the very least hailing it as a welcome alternative to socialism.

Mussolini’s undoing was ultimately his infatuation with military expansion. Like so many Despots of the 20th century, particularly those who were strongly influenced by fascism, Mussolini was a dreamer. Yet there was a huge gulf between his “visions” and practical reality. He saw Italy as rising again to the all-conquering glory of the Roman Empire. Yet the Romans at their height were bold and imperious warriors and statesmen who produced the most efficient and effective military force the world had yet seen. Modern Italy was a relatively minor European power with a weak, ill equipped and reluctant fighting force. Mussolini had brought some semblance of economic and social stability back to Italy (at the expense of personal liberty and an ultimately horribly stultifying state structure) but that was it. He had not done anything to return Italy to anything like its past glory, a task that was way beyond the scope of his talent and imagination. It’s hard to get away from the fact that Mussolini was just another jumped up little militant parading around in a uniform and silly hat, making himself out to be something he could never be. Which is largely the case with so many Despots. They are remarkable only for their mediocrity. All the carefully managed propaganda in the world, ultimately, can’t change that. Mussolini was no Julius Ceaser.

At first, Mussolini’s campaign of expansion got underway reasonably well. He did, after all, pick a fairly weak target – Ethiopia – by then a pale shadow of the mighty Empire it had once been. Even then, the Italians made rather a meal out of it. It took a good seven months to subjugate the primitive Ethiopian forces, before Italy’s superior air power eventually proved decisive. Mustard gas was used against not only the Ethiopian forces but against the civilian population. Some 35,000 Ethiopians perished in Italian concentration camps, maintained for years after the initial conquest was over. Executions and massacres took place. Many thousands died in the starvation and displacement inevitable under a military occupation. All told the war probably resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians. Italian casualties were relatively small, around about 5,000 dead.

Mussolini had managed to expand Italy’s African “Empire”, but one wonders why he really bothered. Ethiopia was hardly the most prized real estate in the world at that point, and he lost it a few years later in World War II anyway. Most European powers (including Italy) already owned significant chunks of Africa between them, of course, but Mussolini’s conquest took place at a time (1935) when further European expansion in Africa was really going out of vogue. The conquest was strongly disapproved of by Britain and France, depriving Italy of what were at one point potentially favourable allies. Nonetheless, the conquest proved to be a huge hit back home. Italy’s Fascist government was never more popular than at this point. Mussolini had not really achieved anything beyond indulging in expansionism for the sake of it, for a futile and self aggrandising dream of Italian glory, but the people lauded him for it.

Mussolini addresses his adoring fans

In 1938, in a move carefully calculated to cultivate Nazi Germany’s support, Italy began passing discriminating laws against Jews, cutting them off from influential positions in public life. It was quite a reversal for Mussolini, who had previously criticised Hitler’s obsession with theories of racial supremacy and proclaimed:

“Race! It is a feeling, not a reality: ninety-five percent, at least, is a feeling. Nothing will ever make me believe that biologically pure races can be shown to exist today. National pride has no need of the delirium of race.”

Actually quite an astute observation, but one later ignored in preference for currying the favour of a fellow fascist state.

When Germany annexed Czechoslovakia on the eve of World War II, Italy abruptly followed suit and annexed Albania. Hitler and Mussolini agreed to a military alliance, dubbed the “Pact of Steel”. However, when the World War officially broke out, with Germany’s invasion of Poland, Mussolini opted to sit back on the sidelines, until the war’s ultimate course looked decisive. In June 1940, with Germany overrunning most of Europe, the safe money was on Hitler. Mussolini suddenly decided to get involved. It was ultimately a rather pointless decision, and proved to be Mussolini’s downfall. Italy could have sat the war out and then consolidated friendship with the eventual victors. But Mussolini saw an opportunity for his dreams of neo-Roman conquest to be realised. He could grab up whatever bits of Europe were slipping through Germany’s fingers.

Hitler never treated Mussolini as anything other than a junior partner, however, and repeatedly withheld the details of his military plans until they were already underway. Rather miffed by such slights, Mussolini decided to go ahead and invade Greece on his own initiative. The campaign was a comedy of colossal fuck-ups, however, forcing Germany to intervene and bail Italy out of trouble. Mussolini was becoming a buffoon and a liability. In fact, Italian forces met with unmitigated disaster wherever they fought, in Greece, Egypt, Libya and the Soviet Union. The tough, disciplined, all-conquering fighting prowess of the Roman legionaries which Mussolini had dreamed of reviving had become, in the reality of the 20th century, a rabble of disorganised and disgruntled peasents carrying cheap rifles. The German high command lamented the fundamental uselessness of the Italian military. “We have the worst allies that could possibly be imagined,” remarked Joseph Goebbels.

By 1943, the Allies were already landing in Sicily. With crushing defeat imminent, Mussolini’s public support abruptly nose-dived. He was deposed by his own party and placed under arrest on an island off Naples. However, Hitler sent a unit of SS Commandoes to rescue Mussolini and bring him back to Munich. Quite why he bothered remains something of a mystery. Mussolini was installed as the “President” of German occupied North Italy – in what was effectively a puppet Nazi government. At this point, Mussolini began collaborating with the Nazi extermination program, and helped to deport some 8,000 Italian Jews to Nazi concentration camps. The vast majority were executed. Earlier in the war, Mussolini had resisted German overtures to deport Italian Jews. Italy had even sheltered Jews fleeing from German occupied territory, despite the institution of its own anti-Semitic laws. However, this was no longer an option under the auspices of Nazi rule.

Meanwhile, the “legitimate” Italian government, situated in the South, signed an armistice with the Allies and declared war on Germany. Italy had broken into two separate states: the German controlled North, and the Allied controlled South.

By 1945, a German defeat was looking like an ever greater certainty. The now widely despised Mussolini attempted to flee to Switzerland, but was intercepted by Italian partisans and handed over to the National Liberation Committee – a guerilla resistance movement opposed to the Nazi occupation. Executed at gunpoint, Mussolini’s body was then strung up and ridiculed by a vengeful public mob.

Mussolini and his pals get the lynch mob treatment

Despot Rating: In many respects, Benito Mussolini’s regime appears relatively innocuous when compared to that of his contemporary and closest ally, Adolf Hitler. Mussolini did not share Hitler’s theories about racial supremacy, nor his murderous zeal in putting them into action. The Nazis were heavily influenced by Italian fascism, particularly with regard to the enthusiastic use of propaganda, centralist economic policies and the use of a paramilitary “bully boy” organisation in the bid for power. The Nazis took the elements of Italian Fascism that they liked and pushed them to the logical extreme.

Mussolini’s regime was an oppressive and stultifying one, but state sanctioned murder was comparatively rare. Mussolini’s worst crime was essentially military aggression – a trait that was hardly uncommon in the first half of 20th century Europe. The history of Europe up until the end of World War II – with Hitler really representing the last throw of the dice for European expansionism – is the history of military conquest.

For that matter, Mussolini’s military aggression was not necessarily markedly different from the military aggression of modern, democratic powers such as the United States. Mussolini fought wars for the old school purposes: capturing territory and winning national glory; the US fights wars these days to secure resources and open up markets. It’s still aggression. It’s just dressed up in different clothing. The invasion and subjugation of Ethiopia was a brutal and destructive one, but not necessarily any more brutal and destructive than say, the US led Coalition invasion of Iraq.

Italian Fascism strongly influenced perhaps the most disturbing and destructive political trends of the 20th century. But Mussolini himself was little more than a jumped up bully boy. Guys like that are a dime a dozen. Hell, you probably want to school with a few of ’em.

* 3.5 Hitler moustaches / 5 for Benito Mussolini

Thank you for a wonderful, entertaining and very educative write up. I learned a lot, laughed in the process and was inspired to read more, a delightful combination.

Thanks mate – glad you enjoyed the article.

Great read,learned things I did’t know before,and you inform in such a way as to make it an easy read.

Thanks,

Stan

bu mussol�n� tam bi �erefsiz ve pi�mi�

Another great read!

The similarities between the events described in the above discourse and current American events is alarming. As a patriot (with only modest levels of courage), I would have liked my nation to remain at the top of the heap for a really long time, and use the power of example, followed by imitation, to infect the world with democracy and general coolness. Now, Italians went stupid on themselves, buying into Mussolini’s bull. I think that perhaps consumerism, taken to it’s current heights, has made dazed and confused wimps of my countrymen. Drugs laid low the hippies and inherent addicts, booze sidelined the tough guys, and the average guys who, by the way, won WWII for us, have now been hobbled by consumer goods acquisitions. Our homes are being repossessed, but we’ve got a pickup truck, a classic car in the garage, a bass boat, a late model small car to commute to work, a house full of stuff, and kids who have all the electronics. If crisis comes, we can’t grow our own food, heat our own houses, or even keep our own houses. We can get our rifles out and shoot somebody, but who? If we slaughter every last person on the dole, and I mean all inner city blacks, all illegal Mexicans, all retirees on Social Security, everyone laid off and collecting unemployment, will that balance the budget? Actually, it might. Only one problem. The powerful crooks who steal from us now, who throw the disfunctional dispossessed people in our faces so that we can hate them, will find ways to keep right on stealing from us. Italy was seduced by the charisma of Fascism because it was in a confused place, and people didn’t want to think for themselves. All discourse in today’s America results in falsity being trumpeted as truth. When you’ve got a talk show, and you can stop anyone from disagreeing with you by just pressing a button on the broadcast studio desk, where will truth find a home, with noble defenders? Honesty is the answer, but how to get there? The press is co-opted. Not ONE mention of Benazir Bhutto telling David Frost that bin Laden is dead. Nothing. And no reaction from the public about this glaring dead giveaway of THE FIX. Of course, the public doesn’t know about the Frost/Bhutto interview. They’re too busy using their computers to buy something.

I love the writeups they are educating and i will need more of them.

WordPress backlinks…

[…]Despot of the Week #7 – Benito Mussolini « The Inquisitor[…]…

The edifice at top of page with the angry face.

What is its name? Are there shots of this building from different angles?

Z.

Hello, I wish for to subscribe for this weblog to take

most up-to-date updates, therefore where can i do it please assist.

Interesting and insightful.

I think you should give him and the Italians more credit for their treatment of the Jews–though he cooperated with the Nazis at the end of the war, 75%-80% of Italian Jews survived.

(except for the comment about the Iraq War at the end).